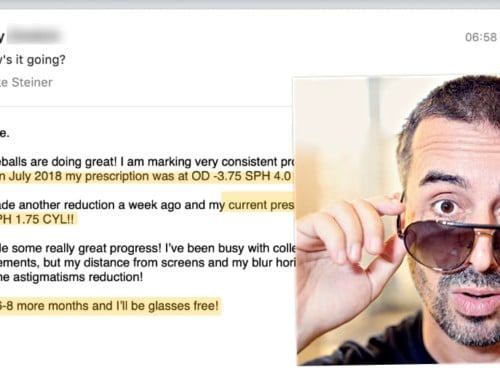

Luke writes:

![]() Six months ago I decided I wanted to get vision correction surgery. I visited an ophthalmologist that specializes in LASEK (sic) for a consultation. To my dismay, the doctor told me I was not a good candidate for surgery due to possible sub-clinical keratoconus. He said there was nothing I could do about my myopia and astigmatism except get regular eye exams to track it’s progression. He said if my eyes continue to worsen I will be at risk for retinal detachment and corneal transplants later in life. Oh, and to top it off he said I should avoid rubbing my eyes because studies have shown that can increase astigmatism. Really, that’s the best advice he can give me: don’t rub my eyes!? Needless to say, I was scared and unhappy after the exam and I did not make a follow up appointment or buy new glasses with the new script.

Six months ago I decided I wanted to get vision correction surgery. I visited an ophthalmologist that specializes in LASEK (sic) for a consultation. To my dismay, the doctor told me I was not a good candidate for surgery due to possible sub-clinical keratoconus. He said there was nothing I could do about my myopia and astigmatism except get regular eye exams to track it’s progression. He said if my eyes continue to worsen I will be at risk for retinal detachment and corneal transplants later in life. Oh, and to top it off he said I should avoid rubbing my eyes because studies have shown that can increase astigmatism. Really, that’s the best advice he can give me: don’t rub my eyes!? Needless to say, I was scared and unhappy after the exam and I did not make a follow up appointment or buy new glasses with the new script.

—

There isn’t a day that goes by that I don’t find myself sighing in front of my computer screen. And this isn’t even just an optometrist, but an actual ophthalmologist dispensing this kind of advice.

If you don’t feel like reading this whole article, I’ll spare you the time: No, rubbing your eyes isn’t going to cause or increase your astigmatism.

So why does Luke’s ophthalmologist suggest such banal nonsense? Where do they find these people? Did they go to school in a barn? Yes, those might be the first thoughts of a somewhat cranky old man, deprived of his morning coffee, coming to terms with having to adjust to a world of e-mail in his sixties (yes, me). But don’t be like me. Choosing an ophthalmologist is like picking an artist you like, a writer you enjoy, a massage therapist who hits just the right spots, a mechanic who manages to keep your car alive when nobody else seemingly can. Medicine, unfortunately today, is still bit of an art (or at least not ideally suited for a mainstream practice, if actual remedy of a chronic illness is your aim).

Here is the thing with being a medical professional: It’s a very long and difficult journey to become a practitioner, and once you are, your life is going to be filled with stress and challenges. Unless you have a love for medicine that outweighs your desire to enjoy a relaxing life, it’s not something you want to venture into.

First, you have the schooling. It’s lengthy and many roadblocks will be put in your path. Entrance exams. Acceptance quotas. And then years and years of study.

Once you graduate, you are far from set. You will have to spend years as a lowly intern, learning a whole lot of things you either long forgot in school, or haven’t actually yet learned. Not the least of which is the aspect of dealing with people and their fears, worries, expectations, and personalities.

You find that it’s not even medicine that defines the challenges of your work. Much harder are the parts where you are responsible for someone’s health, and the way that you deliver diagnosis and advice affects the person’s ability to cope or manage their health challenges. How to manage expectations, and how to communicate becomes a much bigger part of the job than simply gathering information about symptoms, matching them to an illness, and matching that to a treatment plan (that part is often the lesser of a doctor’s challenges).

And that’s not all. You also have to run a business, unless you are practicing in a hospital or as employee in a clinic. If you have your own practice, you have to deal with things ranging from rent or property ownership, to managing employees, dealing with accounting, and a myriad things ranging from office admin software to insurance companies. Imagine filing cabinets for thousands of patients, possibly dozens of new ones on busy days. Not making mistakes becomes statistical fiction, before long.

People say, sure. Cry me a river, Alex. A river of all that money you are making.

If only that were so. Depending on the country we are looking at, some practitioners may indeed earn quite a lot (not so once you account for taxes and employees, if you are working in Western Europe for example – university professors actually often make more, net). Either way though money isn’t going to stop your hair from going gray, from missing out on your children growing up, from high blood pressure, or early heart attacks. Not many doctors (aside from some specializations) are in it for the money, and most would gladly trade wealth for a peaceful life. Believe me when I say this, as I have spent a lot of time surrounded by individuals working in this field.

These days in many countries (the U.S. appears to be championing this, putting lawyer fees as yet another priority over health) you also have to worry about malpractice, being able to pay malpractice insurance, and in some places the proliferation of practices that reduce the value of previously government limited licenses. It’s not worth to many, and in the past ten years I’ve seen scores of professionals quit the business altogether.

All this just as a moment of perspective. When I sometimes may sound derisive about individuals in my field, it’s not a mater of lack of respect. There simply isn’t time to stay up on studies, there simply isn’t the margin of error to start playing around with alternative therapies. The moment a patient leaves your office, the next one is already coming in. Before they come you are dealing with your staff, and after they go you are dealing with paperwork. A lot of your ongoing education, like it or not, does end up coming from the pharma reps (or lens sales, in this particular field). You get up at 5am, you get home at 9pm. It’s not much of a life, unless you happen to venture in a fortuitous specialization.

So we have to give the “don’t rub your eyes or the astigmatism trolls will come and get you” man a break, about his highly questionable assessment about the origins of increasing astigmatism. Yes, it is silly. But in the end all we know is what we are taught, what we have time to read about. In our capacity as far as the client is concerned, we are supposed to identify the symptoms, match known illnesses, and suggest the best course of treatment. As we just looked at, this responsibility makes up just a fraction of our daily duties, and our ability to deliver on this is different for every individual practitioner.

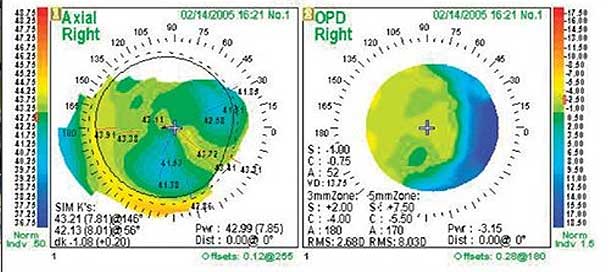

Of course absolutely, astigmatism’s first cause to look at, are minus lenses with astigmatism prescription. The correct question which I would prefer to ask you, rather than rubbing eyes, would be this:

Can we look at all of your previous prescriptions?

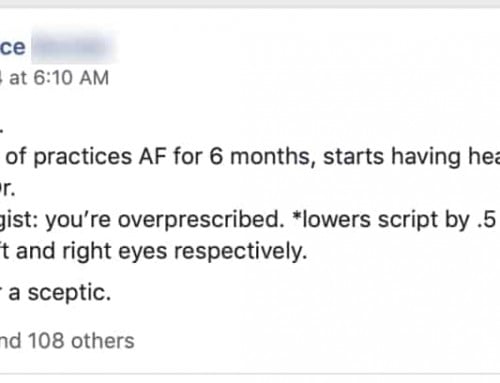

If the sum of previous prescriptions shows a growing curve of astigmatism, in lock step with increase in myopia, then the astigmatism is simply lens-induced. If you don’t want more of that astigmatism, you have to stop accepting prescription increases, and start looking at a rehabilitative alternative for your astigmatism and myopia treatment plan. This though is not taught in school, and it’s not what you’ll hear from the lens sales guys. So you might never know, as ophthalmologist. And some guy you never heard of on the Internet may be making fun of you, and you would be upset to read it, since your life is already stressful enough without the Web making your clients come in with all sorts of alternate diagnoses.

It’s a tough place for them, and for me (and of course, for you). We have to be patient and show compassion, rather than express anger at the shortcomings of the field. And of course we also have to stay away from those guys, if we don’t want our astigmatism prescription to increase, or have our eyes senselessly cut up by lasers. That’s a profitable racket, speaking of ways to maximize making money in the eye care field.

LASIK, today’s equivalent to the middle ages ice pick lobotomy approach to curing a health problem. Let’s leave it at that, before I develop a permanent twitch from shaking my head.

Do enjoy some healthy eyesight today!