Jake Steiner here, bringing you some more eyesight

basics that the mainstream prefers not to tell you about.

—

Here we will take a quick look at how the premise of accommodation, and more specifically accommodative error play a fundamental role in how your myopia develops. More importantly, we’ll look at how science corroborates the need for specific glasses to be used during close-up, to reduce your risk of developing myopia.

Alex is very much focused on the practical aspects of myopia rehabilitation, skipping a lot of the science details that lead to the practices he prescribes for you, here at his site.

It’s fascinating though, the amount of knowledge and specifically the details of it, that drives the seemingly simple habit changes you adapt into your daily life. I quite enjoy his approach, since it gives you the fastest, most tangible access to eyesight improvement activity. You are never forced to contemplate any of the dry academic materials that create the “end user” topics. A great example of it is one of Alex core tenants: While reading / using a computer / screen, always be wearing a specific prescription intended for close-up use.

Of course Alex does explain why, in simple terms. Your myopia symptom limits your distance vision. Glasses only correct one focal plane, intended to help your distance vision. Wear those same glasses up-close, and you create more myopia.

That’s palatable, straightforward, and close enough for most people. It’s a good compromise, for a rehab focused site.

There is so much though to all of this, that I think you don’t get to fully appreciate, without delving a bit further into the why’s and how’s of the subject. There are hundreds of massive studies on the subject of close-up lenses, done with dozens and hundreds of participants, over the course of half a century, all disagreeing with each other. The military has done them, lens manufacturers have sponsored them, the holistic contingent has added their own variations. You never see or hear about these things most likely, but these debates rage on in academic circles. And very fortunately you end up with a guy like Alex, who takes these tens of thousands of pages of dissertations and studies and conclusions, a whole mountain of discussion, and just gives you the simplest possible verdict.

To appreciate what Alex is doing there, let’s take a more in-depth look at what creates the “differential prescription” part of his rehab approach.

First, you want to understand the premise of accommodation, which drives every last bit of the narrative. Here is a good definition of the term, by Wikipedia:

Accommodation (Acc) is the process by which the vertebrate eye changes optical power to maintain a clear image or focus on an object as its distance varies.

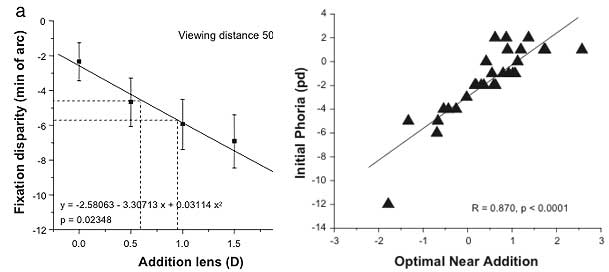

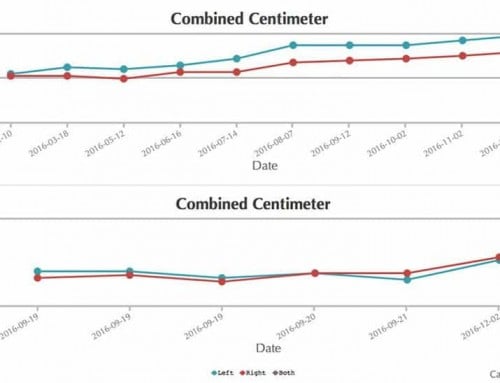

Accommodation acts like a reflex, but can also be consciously controlled. Mammals, birds and reptiles vary the optical power by changing the form of the elastic lens using the ciliary body (in humans up to 15 dioptres). Fish and amphibians vary the power by changing the distance between a rigid lens and the retina with muscles. The young human eye can change focus from distance (infinity) to 7 cm from the eye in 350 milliseconds. This dramatic change in focal power of the eye of approximately 13 dioptres (the reciprocal of focal length in metres) occurs as a consequence of a reduction in zonular tension induced by ciliary muscle contraction. So that makes sense, right? Accommodation is the “auto focus” in your eyes, the means by which you can see both near and far clearly. Accommodation is affected, to a great extent, by the glasses you put in front of your eyes. So much so, that it’s fair to say that accommodation is the key topic in the development of myopia. Science, of course, agrees. In March of 1999, Ophthalmic and Physiological Optics published one of the many articles on the subject of accommodative adaptation, and accommodative error. Here’s the quick summary version: Accommodative adaptation, resulting from the sustained output of slow blur-driven accommodation during the course of a sustained near-vision task, has generally been assessed under open-loop conditions. This study examined whether adaptation influences closed-loop accommodation during the course of a sustained near-vision task. Accommodative adaptation was assessed in 18 fully-corrected subjects by comparing pre- and post-task values of dark accommodation recorded objectively with an infra-red optometer. Subjects performed a continuous 10 min binocular near-vision task at a viewing distance of 33 cm, with the within-task accommodative response being assessed at 1 min intervals during this period. Subjects were categorized into adaptors (N=11) and non-adaptors (N=7) on the basis of whether their initial 10 sec post-task adaptation exceeded +0.30D. The adapting group exhibited a significant decline in the lag of accommodation during the first 3 min of the near-task, whereas no significant change in the within-task response over time was observed in the non-adapting group. These results indicate that accommodative adaptation increases the accuracy of the within-task, closed-loop accommodative response. Furthermore, we speculate that a deficit in accommodative adaptation, being accompanied by increased retinal defocus during near fixation, may contribute to the development of nearwork-induced myopia. — The emphasis is there in the last sentence is mine. Original article and download options are here. If you are into this subject, it’s quite the dead horse of a subject. Yes of course, accommodative response and the accommodative error in particular, create a myopic symptom. Here’s what matters: If you wear your regular distance prescription for close-up, you get a *lot* of accommodative error. Depending on genetic predisposition this will translate to less or more myopia, sooner or later. It’s not a question of *if* but rather of *when* and *how much*. If you don’t need glasses, close-up will still produce accommodative error. This error creates a real myopia risk. So what does Alex do when he talks to you about fixing your myopia? One of the first things, without too much technical details, he tells you to adjust your prescription for close-up use. It’s the same thing I do, though I never took Alex’ quite so elegantly simplified approach (hey, it works!). Alex took a whole lot of science, and boiled it down to a proposition that is very simple and very elegant: Use only as much correction as you need to get a blur horizon at your ergonomically comfortable distance. This is truly brilliant, especially if you come from my position. I’m the guy who read the tens of thousands of pages of arguments back and forth, and bought some of the expensive equipment to test on myself. In the end, Alex has the best way. To truly appreciate the magnitude of the simplicity, take a look at this bit of science, published in Optometry & Vision Science in 2008: The study recognizes accommodative error as a problem, and looks to establish exactly how much and what kind of correction is needed for close-up use. Essentially it’s the same thing Alex let’s you figure out quite simply at home, done by guys who take the much, much longer route: Purpose. The purpose of this study was to determine the optimal power value of near addition lenses, which would create the least error in accommodative and vergence responses. Methods. We evaluated accommodative response, phoria, and fixation disparity when the subject viewed through various addition lenses at three working distances for 30 young adults (11 emmetropic, 17 myopic, and 2 hyperopic). Accommodative response was determined with a Canon R-1 infrared optometer under binocular viewing conditions, phoria was determined by the alternating cover test with prism neutralization, and fixation disparity was measured with a Sheedy disparometer. Results. We found that the optimal powers of near addition lenses for the young adult subjects associated with zero retinal defocus were +0.92 D, +1.04 D, and +1.28 D at three viewing distances, 50 cm, 40 cm, and 30 cm, respectively. The optimal powers associated with −3 prism diopters (Δ) near phoria were +0.58 D, +0.35 D, and +0.20 D at the three distances, 50 cm, 40 cm, and 30 cm, respectively. In addition, we found high correlations between the initial accommodative error and the optimal power of the near addition lenses and between the initial near phoria and the optimal power of the near addition lenses. Conclusions. The results suggest that when the effects of near addition lenses on the accommodative and vergence systems are both considered, the optimal dioptric power of the near addition lens is in a range between +0.20 D and +1.28 D for the three viewing distances. Using progressive lenses to delay the progression of myopia may have promising results if each subject’s prescription is customized based on establishing a balance between the accommodative and vergence systems. Formulas derived from this study provide a basis for such considerations. — That’s plenty right there to give you a headache. Imagine reading not just this, but the accompanying full PDF of the study. It’s interesting though, even if the details are dense. There is clearly not only an appreciation in optometric science that close-up use is responsible for accommodative error, and that this error takes notable responsibility in the development of a myopic symptom. The evidence is significant enough that studies are conducted not just about the accommodative error, but how glasses play into correcting specifically for close-up use. There are others out there who recommend adjustment for close-up use. You’ll find things like “plus lens therapy”, which often is proposed by individuals who don’t fully understand the drivers behind the concept. That’s a pretty common one online, and it concerns me because the lack of understanding opens the door for a whole lot of misuse and lack of positive results. Then there are those who propose the use of lower prescriptions, also often without demonstrating an understanding of the “why” of that course of action. Again, there is a problem with presenting something without fully understanding the full picture, as it creates a risk for misuse. And finally you get behavioral ophthalmologists who take accommodative error and attempt to compensate for it, by offering a correct close-up prescription. I’ve met a whole lot of these guys over the course of my career, and they’re the better solution of all the options. They still tend to obfuscate a lot, and remove you from being able to prescribe for yourself. The most brilliant approach is by guys like Alex who have intimate knowledge of the biology and science, and then look for the best way to put all of that into your hands, in a way you can easily use it yourself. Blur horizon based centimeter measurement and resulting diopter correction is a very, very effective way to compensate for accommodative error. You get to the same functional results as the guys from the complex study I reference above, without all the involved steps and measurements. It’s truly brilliant, and sadly not far more popular. To my knowledge Alex is the the only guy out there who gives you this unprecedented level of access to such an inaccessible health science subject. All you need to do is download the diopter measuring tape, figure out your close-up distance, and you’re good to go. And you have the support forum to eliminate the risk of misuse, in case you are confused and need more help. These are the guys who should be dominating the public discourse on eyesight health, instead of being marginalized and running small rehab sites as retirement projects. Another issue with all of this is the extent to which it will have a positive effect on your eyesight, depending on accompanying practices. Just wearing a correction alone doesn’t necessarily give you better vision. Lots of studies end up saying that a close-up correction showed little effect on myopia development, which can leave you confused as to why you’d want to use it for yourself. Again here though, Alex says 1) get a differential prescription and 2) work at the blur horizon / push focus. Lots of brilliant in those two seemingly very simple tenants. As a fellow professional I have deep admiration for Alex’ insights. Two simple sentences addressing the whole mountain of a topic of accommodative error, as well as all that goes into positive stimulus (another article that, entirely). Hopefully this wasn’t entirely too boring, and provided a bit of a glimpse into what happens behind the scenes of your hopefully favorite rehab program. And please do support this site by 1) writing elsewhere on the Web and linking to it (so, so important) and 2) using the paid Web course, if you are working to improve your eyesight. Resources like this will only continue to exist at the grace of your support. Guys like Alex get more grief than it’s worth, and these things aren’t exactly big money makers or providing a whole lot of personal satisfaction. I myself spent the last 10+ years charging thousands of dollars to individual clients, and never even considered going online and giving everything away and dealing with all the Internet troll-dom. I’m helping out because I don’t want to see these little islands of hope getting swallowed up in the ocean of for-profit optometry. If you can do just one thing, it’s to write about your experience online and link back to Alex’ site. Cheers! – Jake Steiner Comments are open for this article. Optimal Dioptric Value of Near Addition Lenses Intended to Slow Myopic Progression