“At the earliest stage, micro aneurysms occur in the eye. They are small areas of balloon-like swelling in the retina’s tiny blood vessels.“

– NEI (The National Eye Institute)

Diabetic retinopathy.

Or, how your eating habits can take you straight into one of the leading causes of adult blindness.

As you read this article, consider the fact that it’s not entirely relevant whether or not you are diabetic. Retinopathy can be a significant risk of your future vision health.

Interestingly enough, you can conceivably avoid this increasingly common and devastating vision illness, by learning to understand your diet’s effects on your blood glucose levels. I’ll provide links to some insightful practitioner’s advice here in a moment.

First things first.

Do you need to worry about diabetic retinopathy?

JAMA, the ophthalmology journal, puts retinopathy high on the list of causes of adult blindness:

Approximately 4.1 million US adults 40 years and older have diabeticretinopathy; 1 of every 12 persons with DM in this age group has advanced,vision-threatening retinopathy.

Much, much worse, the global numbers:

There are approximately 93 million people with DR, 17 million with proliferative DR, 21 million with diabetic macular edema, and 28 million with VTDR worldwide. Longer diabetes duration and poorer glycemic and blood pressure control are strongly associated with DR. These data highlight the substantial worldwide public health burden of DR and the importance of modifiable risk factors in its occurrence. This study is limited by data pooled from studies at different time points, with different methodologies and population characteristics.

Published in NCBI.com, “Global prevalence and major risk factors of diabetic retinopathy“.

Other sources estimate the incident rate even higher:

Diabetic retinopathy (DR), a major microvascular complication of diabetes, has a significant impact on the world’s health systems. Globally, the number of people with DR will grow from 126.6 million in 2010 to 191.0 million by 2030, and we estimate that the number with vision-threatening diabetic retinopathy (VTDR) will increase from 37.3 million to 56.3 million, if prompt action is not taken. Despite growing evidence documenting the effectiveness of routine DR screening and early treatment, DR frequently leads to poor visual functioning and represents the leading cause of blindness in working-age populations. DR has been neglected in health-care research and planning in many low-income countries, where access to trained eye-care professionals and tertiary eye-care services may be inadequate. Demand for, as well as, supply of services may be a problem. Rates of compliance with diabetes medications and annual eye examinations may be low, the reasons for which are multifactorial. Innovative and comprehensive approaches are needed to reduce the risk of vision loss by prompt diagnosis and early treatment of VTDR.

From the Indian Journal of Ophthalmology, “The worldwide epidemic of diabetic retinopathy“.

Retinopathy is as much a potential end to life as you know it, as it can be prevented in a large majority of cases.

It’s an ugly way to lose your vision.

Consider a slow and ongoing degradation of your eyesight, knowing that you can’t stop it, knowing that it’ll just keep getting worse.

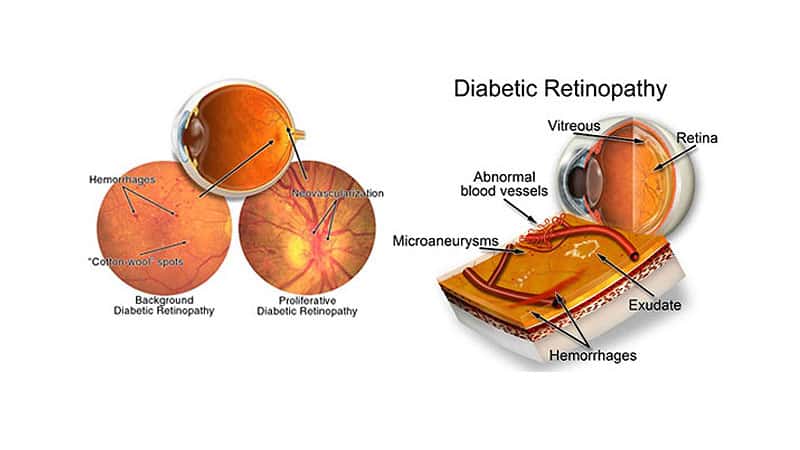

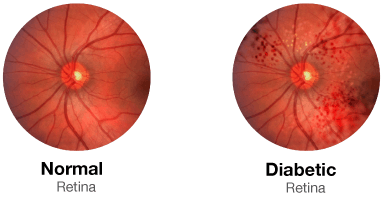

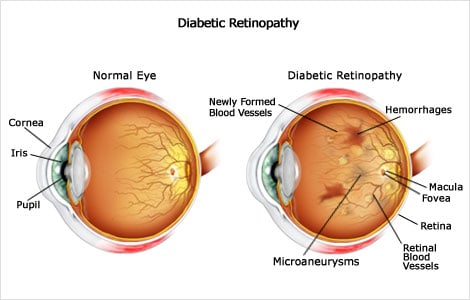

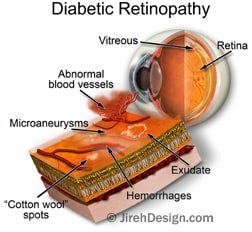

Diabetic retinopathy, a retinal vascular disorder that occurs as a complicationof diabetes mellitus (DM), is a leading cause of blindness in the United States,often affecting working-aged adults.1 It ischaracterized by signs of retinal ischemia (microaneurysms, hemorrhages, cotton-woolspots, intraretinal microvascular abnormalities, venous caliber abnormalities,and neovascularization) and/or signs of increased retinal vascular permeability.Vision loss can result from several mechanisms, including neovascularizationleading to vitreous hemorrhage and/or retinal detachment, macular edema, andretinal capillary nonperfusion.1

We tend to start to care about these things when it’s really quite late to do anything. And you might say, well Jake. I’m not diabetic. Besides, aren’t these things genetic?

Is retinopathy genetic?

Let’s look at some proper studies in context.

The prevalence and features of diabetic retinopathy have been examined in twenty-three pairs of identical twins—thirteen concordant (both diabetic) and ten discordant (one diabetic, one not)—who have had diabetes for at least fifteen years. In the concordant pairs retinopathy was more common (present in twenty-three out of twenty-six individuals) and more severe (seven blind or partially sighted) and a family history of diabetes was more frequent than in the discordant pairs (retinopathy in five out of ten, none blind). In twelve out of the thirteen concordant pairs the progression and severity of retinopathy was strikingly similar in the two twins and was correlated only with the duration of diabetes. In the thirteenth pair after twenty years of diabetes, one was blind and the other had normal eyes, although they showed no obvious differences in control or other features. It seems that genetic factors may be important in the etiology and time of appearance of diabetic retinopathy.

That one is published by the American Diabetes Association, in “Diabetic Retinopathy in Identical Twins“. As usual, genetics play a role.

And as also-usual, you are not helpless in determining your eyesight’s health future.

In “Pathogenesis of Diabetic Retinopathy“, we find out that even with diabetes, the onset of retinopathy can be delayed, if not entirely managed:

Diabetic retinopathy involves anatomic changes in retinal vessels and neuroglia. The pathogenetic mechanism responsible for retinopathy is imperfectly understood, but much of the mechanism is apparently reproduced by experimental diabetes in animals and by chronic elevation of blood galactose in nondiabetic animals. The evidence that retinopathy is a consequence of excessive blood sugars and their sequelae is consistent with a demonstrated inhibition of retinopathy by strict glycemic control in diabetic dogs.

There are a number of research articles on the subject of mitigating the effects of diabetes on the retina, such as the lengthily titled “Effect of Multiple Daily Insulin Injections on the Course of Diabetic Retinopathy“:

Forty-two diabetic patients on insulin once a day in the early stage of diabetic retinopathy were randomly assigned to one of two kinds of insulin regimen, i.e., single or multiple daily injections. Retinal changes were quantitatively estimated by counting the microaneurysms (MAs) observed on fluorescein angiograms at the posterior pole of the more diseased eye. Baseline characteristics of the two groups were not significantly different. These included duration of diabetes, age at diagnosis, daily dose of insulin, amount of urinary sugar excreted in 24 hours, fasting blood sugar (FBS), and number of MAs. During the follow-up (mean duration of three years) the mean yearly progression in the number of MAs was significantly less in the multiple-than in the single-injection groups.

And as usual, a whole lot of modern medicine waits till you are in full blown symptom mode, before sprinting into action.

Don’t wait till this applies to you.

But you don’t want symptom mode. Take a look:

- Mild Nonproliferative Retinopathy. At this earliest stage, microaneurysms occur. They are small areas of balloon-like swelling in the retina’s tiny blood vessels.

- Moderate Nonproliferative Retinopathy. As the disease progresses, some blood vessels that nourish the retina are blocked.

- Severe Nonproliferative Retinopathy. Many more blood vessels are blocked, depriving several areas of the retina with their blood supply. These areas of the retina send signals to the body to grow new blood vessels for nourishment.

- Proliferative Retinopathy. At this advanced stage, the signals sent by the retina for nourishment trigger the growth of new blood vessels. This condition is called proliferative retinopathy. These new blood vessels are abnormal and fragile. They grow along the retina and along the surface of the clear, vitreous gel that fills the inside of the eye. By themselves, these blood vessels do not cause symptoms or vision loss. However, they have thin, fragile walls. If they leak blood, severe vision loss and even blindness can result.

That ones is from NEI, the National Eye Institute, in “Facts about Diabetic Eye Disease“.

Hopefully that’s enough fear mongering to get you to put the Coke down, and take a look at what some medical practitioners suggest on this whole topic.

The real story starts with blood sugar.

To explain, in actionable terms, let’s look at Chris Kresser’s suggestions. As always, consider these pieces just starting points for your own research (ie. I”m not telling you to specifically listen to just one person on the subject).

Prolonged exposure to blood sugars above 140 mg/dL causes irreversible beta cell loss (the beta cells produce insulin) and nerve damage. 1 in 2 “pre-diabetics” get retinopathy, a serious diabetic complication.

This is important. You don’t have to be diabetic, to be at risk of retinopathy.

Hemorrhages. In your eyeball.

That’s from Chris’ article “Why your normal blood sugar isn’t normal“, which is recommend you take a look at. There is also Part I of that two-part article.

Related, there is also a very simple, actionable way to look at your own blood sugar that Chris recommends. While this is obviously a topic far larger than we could do justice here in one post, I suggest you explore a bit. At least make sure your blood sugar is in normal range, consistently.

Why all this, now?

I notice a disturbing increase in students with retinopathy in various stages, lately. Just this week I had three new inquiries from prospective students with the condition. And in every case it seems to come as a notable surprise, accompanied with very little in terms of non-pharma related treatment advice.

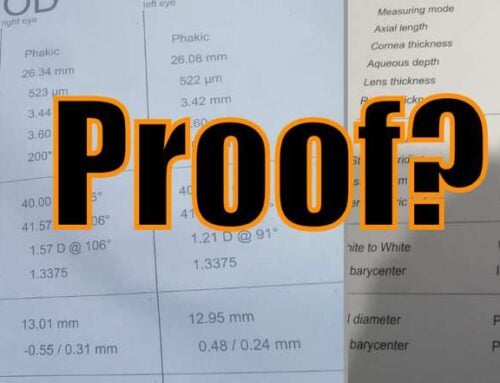

Take care of your eyes. Make sure all those blood sugar bits are in normal ranges. A $16 dollar blood glucose meter, a few quick tests is all it takes to check in and make sure:

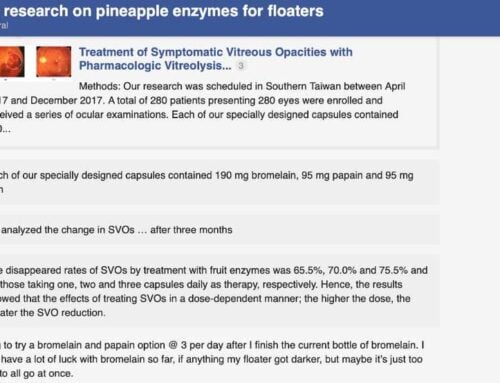

| Marker | Ideal* |

| Fasting blood glucose (mg/dL) | <86 |

| OGGT / post-meal (mg/dL after 1 hour) | <140 |

| OGGT / post-meal (mg/dL after 2 hours) | <120 |

| OGGT / post-meal (mg/dL after 3 hours) | Back to baseline |

| Hemoglobin A1c (%) | <5.3 |

Simple things. It’s always simple things, if you start early.

Centimeters, eye charts, becoming aware of eye strain. Making sure that your food isn’t making you ill. It’s always small corrections that can do the trick. Doing that early, instead of waiting for the doctor to sell you on a lifetime of prescription symptom management.

And as always, a starting point for your own investigation. Never take anything here as listen-only-to-Jake edicts.

Cheers,

-Jake