Allan Hytowitz claims to have invented a new way to measure visual acuity.

The real question is: Did this guy just leap ahead of every eye chart you’ve ever seen, with a brilliant new way to measure eyesight and myopia?

Or is it all just crazy talk? Stick around, find out.

Yesterday I cheated a bit, and covered several topics (and two Youtube videos!) in one post. It’s the only way to start clearing some backlog, get ahead of the blog and get into other topics I really want to introduce you to.

So much goes on behind the scenes, and most of it I never bring up here.

Weird things. Brilliant things. Things that could be weird, or brilliant, or both. Sometimes you look at something and you just can’t tell for sure.

Here is one, that’ll I’ll leave up to you to judge.

I’m digging this one out of the rather large pile of e-mails I get, trying to get me to talk about new products, or old products, various conspiracy theories (hey, you never know), and a lot of science discussions that (for whatever reason, certainly not me asking for it) I seem to always be cc’d on.

So you know about Snellen. Eye chart, invented back in the day (early 19th century). It was revolutionary in its day, as it standardized acuity. Back before we knew anything about anything.

And just like glasses have been around since the 16th century (some say earlier than that), the Snellen endured the test of time. For hundreds and hundreds of years we’ve been using this and various conceptually similar permutations, to judge eyesight and determine lens prescriptions. As super cool as humans are with amazing inventions on one hand, we sure do like to stick with tradition on the other (with “medicine”, which I’d say is a little scary).

Your ATM machine software is several hundred years more up to date than the medical test that determines whether you will wear a permanent focal plane prosthetic over your eyes, for the rest of your life. How much has humanity learned about vision and human eye biology, in the past one hundred years? A staggering amount (everything, basically). And yet we still use tests from before we learned most of what we know, and “treatments” that even predate the tests (lots of curious ironies and logical inconstancies in all of that).

But just like nobody will look at myopia seriously, leaving the mess in the hands of guys like your favorite eye guru, the tests that determine your vision “health”, are apparently permanently not getting updated. And curious individuals step in, coming up with more 21st century solutions of their own.

Disclaimer, here, before we go further:

Your darling Jake is more like a plumber, than a fancy mathematician, in the scheme of things. I can help you fix your myopia, I’m reasonably decent at that. Herding a bunch of type-A personalities, get them to pay attention, get them to want to partake, nudge them to tweak habits. I’m very less the guy you want to look to for a thumbs up, or a thumbs down on what you’re about to look at. It’s certainly interesting enough to warrant talking about, the rest I leave to you.

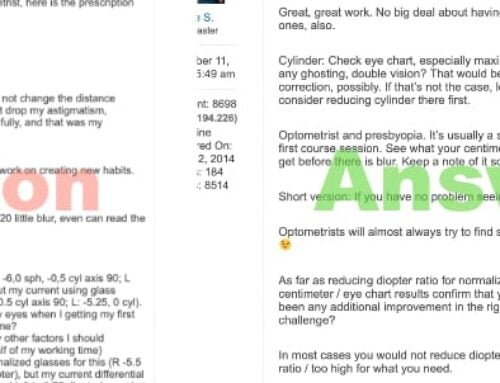

Here’s what Allan says, about his tools for measuring acuity:

We see the world as pixels, and not as lines and shapes.

Our bodies are biological machines. Our eyes developed as sensors for detecting motion, distance, and colors so that humans could better detect predators and game, and eat rather than be eaten.

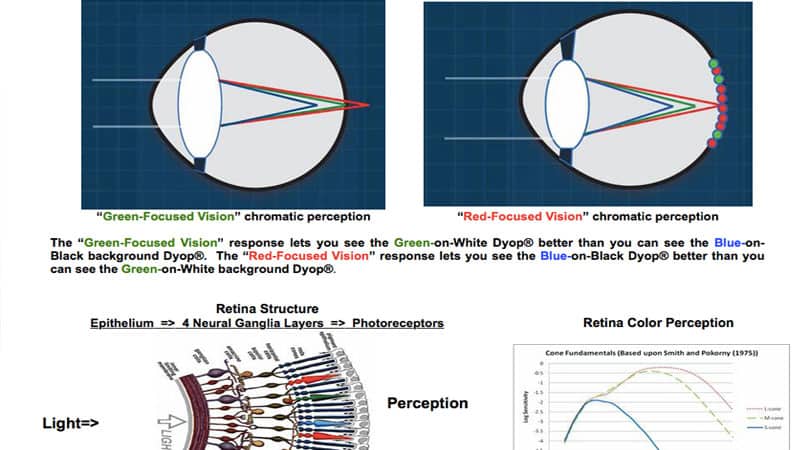

However, the images we see are actually pixels rather than lines or shapes. The neurons of the retina convert the photoreceptor pixel stimulation into those lines and shapes. The retina takes the pixelized stimulus of about 100 photoreceptors and merges them into the stimulus of one optic nerve fiber before transmitting that impulse to the brain. As light is transmitted and focused by a properly functioning biological lens, it also fractures the wavelengths of light. That color disparity typically has the color red focused slightly behind the retina while the color green is typically focused on the retina. The disparity of that red/green perception is also transmitted to the muscles controlling the focus of the biological lens which in turn regulates its focus length

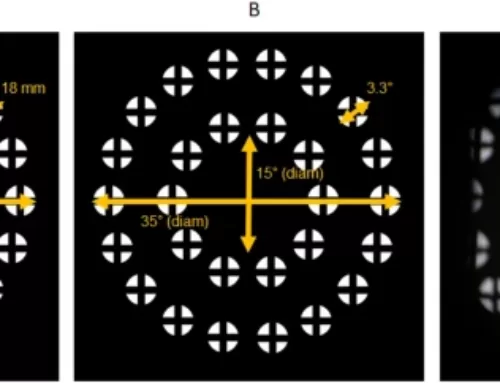

A Dyop® (short for dynamic optotype) is a rotating segmented strobic gap/segment visual stimulus which utilizes the photoreceptor pixel perception to measure visual acuity. The strobic stimulus of the moving black/white-on-gray Dyop® gap/segments serves as a on/off switch for photoreceptor stimulus. Much as the lines and shapes we see on a pixelized TV, or other electronic display, we see the lines and shapes when we no longer perceive them as pixels. As the stimulus area of the gap/segment area gets too small, that stimulus becomes smaller than the minimum area of photoreceptor visual resolution. The minimum stimulus area which lets us see the Dyop® gap/segment motion as a pixel-type stimulus is the acuity endpoint and provides a very precise, accurate, and efficient method for determining visual acuity.

If you dig biology and science, your curiosity has to be tickled right now. Super interesting ideas, right?

There is a whole lot more that Allan would like to show you, over at http://www.dyop.info. His site, which I can’t imagine how much work must have gone into creating it all, includes the actual testing tool (which you can set up to work on just about any device).

Allan doesn’t get much love from the mainstream. And while I don’t pick allegiances, it is sometimes curious to just what extent interesting solutions are ignored, just to maintain the status quo (and not make the cash cow look bad).

If you’re curious about this sort of thing, tinkering and development going on below the radar of the mainstream, definitely check out the Dyop. Feel free to start a forum discussion, perhaps there are other geekily inclined students over in BackTo20/20 (meant in the most flattering way, naturally). A lot more to potentially be said about this topic, Allan’s work, me being a bit of a hypocrite on some level, keeping you using old-timey eye charts. We’ll leave all that for a potential future discussion.

There is quite a bit of stuff like this (perhaps a lot of it a bit less fascinating than Allan’s work), collecting in my archives. I’ll try to occasionally bring you some of this, which are things you’re not likely to find anywhere else online!

Cheers,

-Jake