As discussed in other posts and the Vision Improvement Courses, blur is generally not in any way beneficial to your vision health.

We want to spend most of our time with clear vision, and some of our time at the edge between clear and blur. That edge of focus is where we get stimulus for improvement from, where we experience active focus. Past that edge though, where the image is just blurred, nothing beneficial happens.

Some of us prefer not to wear glasses, no matter what. Depending on myopia degree, this may just be somewhat uncomfortable, or actually dangerous (if you cross the road, or drive without glasses). It is a bit like refusing to use a cane, if one of your legs does not work properly – the resulting walks won’t be particularly enjoyable or safe. Not wanting to wear glasses is an excellent instinct, but sometimes we need to recognize the benefit of using them – to restore healthy vision in the long run.

Still, if you only have very low myopia (below -1.5D) and prefer not to wear glasses, there are some tricks you can use to get past the blur, and even improve your eyesight.

To a larger degree, this topic is important to those who follow the #endmyopia Method for vision improvement. If you just recently started wearing a normalized prescription, you are probably dealing with some unexpected blur. Since this prescription is designed for active focus and eyesight improvement, it will make you work for focus – and in this post, we will briefly discuss some tricks of just how to do this.

Your normalized prescription may range from conservative to aggressive. On the aggressive end of the scale you will experience a lot more blur, but also more opportunities to pull focus and work on your active focus.

Here is how to deal with the blur from normalized prescriptions – or no glasses at all:

First, you want to define your focal range.

This means figuring out just how far you can see without blur, at what distances blur happens, and how much further you can see before blur is preventing you from getting a usable image. This is important for practical reasons (how useful is this prescription, for driving?), as well as for your vision improvement goals.

Keep in mind too, that a normalized prescription has a more limited ambient light range than a full prescription. Depending on how aggressive the prescription is, you may loose quite a bit of distance once lighting gets less than sunny, or you are dealing with substandard indoor lighting. Factor this in when you define just how far you can see, with your new prescription.

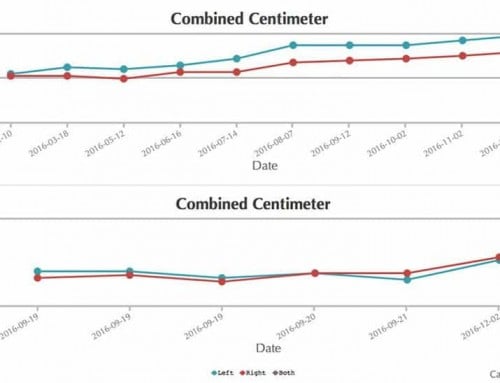

Keep a note of distance in your log – that way you can compare down the road, how much your vision improved.

Use distant writing, making your own impromptu eye chart out of street signs.

There is a reason that eye charts use letters. Instead of just looking off into the distance, wondering if blur is blur, look for writing. Can you read the street sign at ten meters? 15? 20? Street signs are great, because they tend to be of consistent size and font type, giving you a consistent frame of reference. Reading also allows you to accurately gauge blur. If you can read it, you are still in the range of the edge of blur, and that distance is usable for your normalized prescription (or no glasses).

Let’s get back to my wheelchair vs. crutches analogy for a moment (you may have seen it in other posts):

If you hurt your leg and opt to sit in a wheel chair, you are not giving your leg opportunity to get strong again. If you use crutches, you won’t be very comfortable, but you are forcing your body to regain its function.

With a crutch, you quickly learn about your leg’s limitations. How far can you hobble, before you need a break? What about hills? Stairs? With crutches, you are actively participating in what your body is capable of, and you have the opportunity to push yourself. This is a normalized prescription. The full eyeglass prescription, that 99% of optic shops will prescribe, is the wheel chair – it’s easy, comfortable, no effort. And you get zero benefit, your leg muscles will become useless, and you will always need that wheelchair (unless you switch to crutches, the #endmyopia Method way).

You want to know these crutches style of limitations, with your normalized prescription. Street signs, your distance to them, and lighting conditions – keep them in a little log, so you can refer back to it a month, three months, or a year from now. It will be excellent encouragement, believe me!

Any time you put on that normalized prescription and the world looks a bit blurred, find some writing. Focus on it, feel free to walk towards it, stop when it becomes legible. Try to pull it into focus more clearly. That effort, at that edge of focus, will give you the most of your assisted (crutches) focal plane change from your normalized prescription.

Wrap Up

The long and short of it, use text to define whether the distance is too great, or usable. If you can read the sign, the distance is good. It isn’t really important how much distance you get (except when you are driving, please be safe!), just that you work at that distance, whenever you think of it, pulling some focus.

You can be passive about the distance, and not try to pull distant text into focus. But then you are not improving your vision. The way to work with blur, and define it’s edges, is to create your own eye chart out of distant writing!

Enjoy,