Semi-pro topic, this one. A supportive optometrist is a great idea for any type of lens adventure. Be aware of local laws regarding prescription lenses. This as usual, not optometry or medical (as if!) advice.

Sometimes we get students, just starting out with BackTo20/20, already having changed their distance lenses, as well as the close-up. Not ideal! This erroneous approach tends to manifest in forum posts, trying to untangle what now doesn’t flow with the initial set of instructional sessions.

I explain the reason why I discourage changing both close-up and distance at the same time (for the first time), again in a recent forum thread:

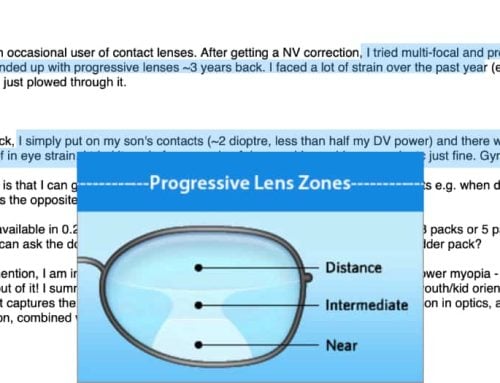

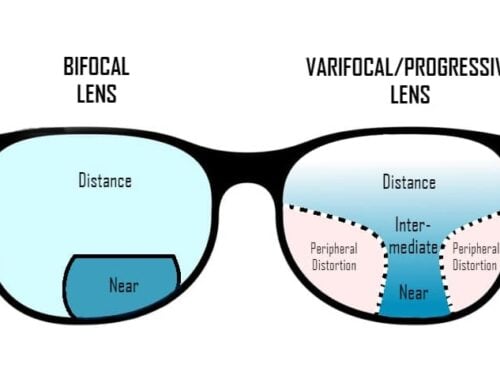

The course deals with close-up first (since that’s the most common user scenario). We don’t want to change both primary focal planes at the same time (close-up and distance), to avoid introducing too many variables. Also, it’s likely that your vision will change notably in a matter of weeks, with active focus stimulus and less strain. So we go differential first, and then 4-6 weeks in we look at centimeter changes, see what may have to be adjusted, and then pick a new distance prescription based on it. This also preserves the diopter ratio across prescriptions (important), and reduces the time to adjust to a new distance prescription notably.

Understanding how prescription lenses work, even with the systematically tweaked simplification, takes a moment or two. You don’t want to mess with lenses, until you properly understand how they work.

Then you want to understand how diopters affect your vision. You need to actually learn what the blur horizon is, measure it, and make an assessment how that translates to the diopters you need.

We make this as simple as possible (and it’s quite elegant, dare I say). But it’s still an undertaking. And the first differential (close-up lens) is going to be a bit of a “best guess” scenario. Why?

You might opt to remove astigmatism correction for close-up. You may be looking at correcting diopter ratio between left and right eye, if your own measurements don’t reflect your current prescription numbers. And then, with all that done, and ideally correct, you’ll still realize that in a matter of weeks that close-up correction is stronger than you need.

That could be the case even if you did get it right from the start. And yet, with some active focus experience, lowered strain, and just a few weeks of time, your vision may have measurably improved. This means of course, another reduction.

Take all of the above into account. Would it be a good idea to complicate this experience, by doing all of this for a reduced distance prescription at the same time? It’d be not fun and likely stressful!

Instead of doing that, it’s ideal to keep the familiar distance correction, until at least the first successful close-up (differential) reduction. My rule is to pick your normalized (reduced distance prescription) along side of your second differential (close-up) lenses. At this point your first bit of improvement has told us what we need to know about your vision, you know how to measure, and you know that reduced distance prescription will be the correct one.

And it eliminates all the potential stress, second guessing, and you don’t expose your visual cortex to all sorts of unnecessary potential strain in the process.

You also save some money this way, you keep a familiar distance focal plane, your brain is happy, and you don’t mess with the much more critical distance prescription (critical for actually seeing clearly at a distance) until you’re ready for it.

Structure is key. You can go mess around with lenses, not with this approach, but odds are that you won’t enjoy that outcome.

All of these things, based on a decade of experimenting, trial and error, understanding vision biology and optics, conferring with friendly professionals, getting feedback from participants. I try to share as much as possible in the blog, to enable you to take care of your eyeballs, even if you can’t get a spot in BackTo20/20. If you like these guides, say thanks via e-mail, or comment on Twitter, or our friends and family YouTube channel.

Cheers!

-Jake